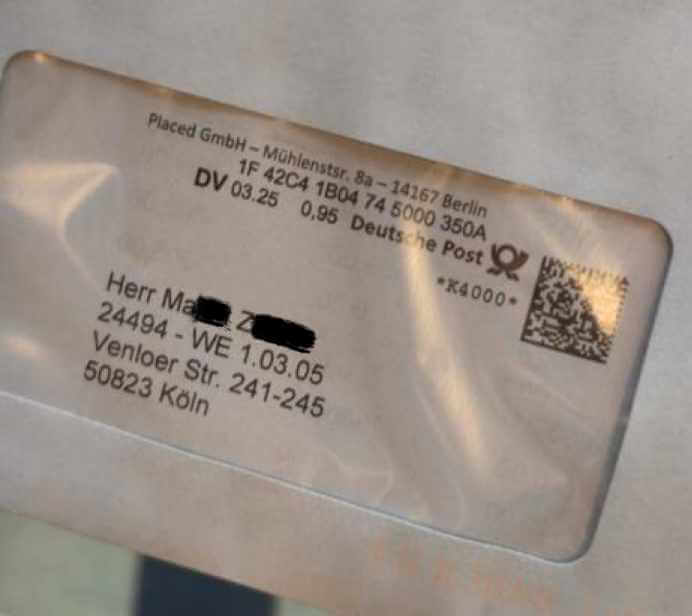

Cologne-Ehrenfeld, Autumn 2024. At the so-called “4711 House” on Venloer Straße 241–245, strange occurrences begin to pile up. The same men are repeatedly seen loitering outside the building — strangers who don’t behave like regular visitors but instead head purposefully to specific apartments, often accompanied by young women who appear to be “working” there.

The dormitory, officially designated as student accommodation, is increasingly being used for other purposes. Soon, rumors begin to circulate: prostitution in the middle of a student residence?

At first, there are only quiet observations — occasional noise complaints, unsettling encounters in hallways. But by spring 2025, the full extent becomes apparent: the building is the site of suspected forced prostitution. Young women, primarily from Eastern Europe, are servicing clients in student-style rooms — systematically, under supervision, and apparently under pressure.

A pimp is regularly seen outside the entrance; men come and go. Other students report harassment, fear, and sleepless nights. The emotional toll mounts. Some can no longer cope and move out.

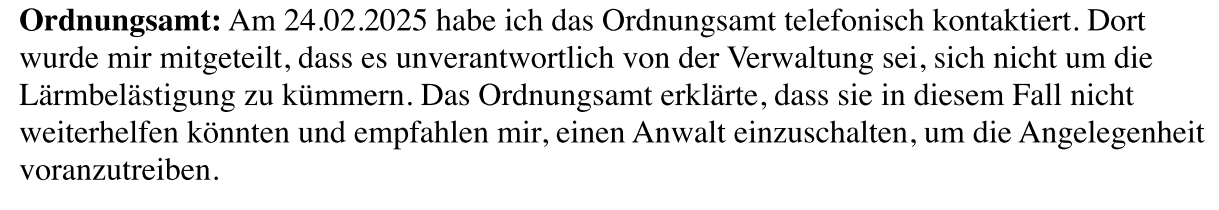

The residents turn to the landlord, property management, and local authorities for help. But instead of support, they receive bureaucratic requests: noise logs, complaint forms. The situation remains unchanged.

"I had to fill out reports like that for them four times."

– L., Student, nach Kontakt mit der Hausverwaltung

We are in contact with the students and, at their request, are documenting the events at the 4711 dormitory – a chronology of failure that once again highlights how our laws fall short when it comes to effectively addressing sexual exploitation within the legal framework of prostitution.

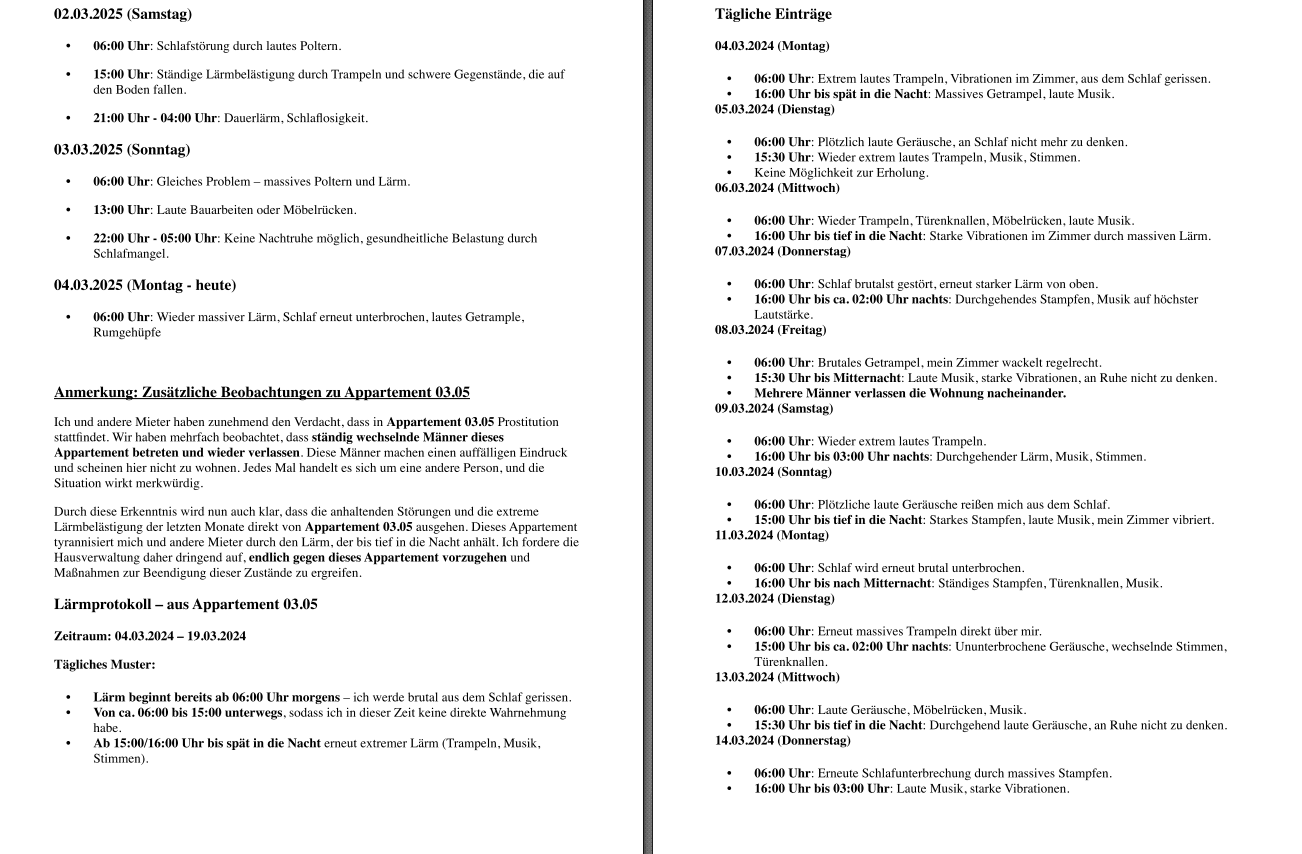

From around October 2024, noise disturbances were first reported coming from room 305 — coinciding precisely with the official move-in of Ma. Z. Prior to that, the room had apparently been unoccupied or at least completely silent for an extended period.

Between October and February, there were multiple instances of knocking on the door of room 305. Almost always, a woman named Gi. E. answered — frequently accompanied by different men.

Reports about the noise disturbances led to no change in behavior.

The building is divided into several usage areas:

The hotel starts from the 5th floor and has its own entrance with a reception area at street level. Access to the hotel is either through this separate entrance or—if equipped with the appropriate key fob—also via the student dormitory.

Students do not have access to the hotel area.

Rooms 305 and 425, both located within the student dormitory section, are repeatedly mentioned in connection with suspected prostitution.

The residents of the dormitory repeatedly complained to the property management — not only about the suspected misuse of living space but also due to specific everyday disturbances: clients approach other female students, knock on doors, and from some rooms, there are regular nighttime noises of furniture being moved, stomping, and screams that can be heard in other units.

Until January 2025, Corestate Capital Group was responsible for managing the dormitory. Despite multiple complaints from students, they did not respond.

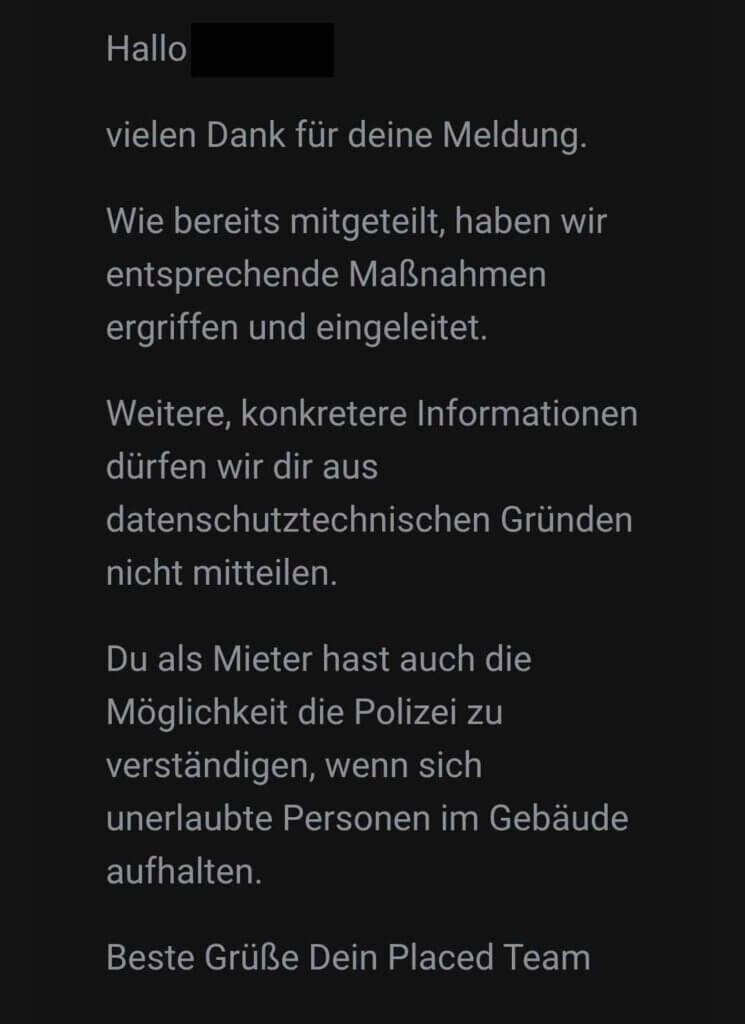

At the end of January 2025, the company Placed took over property management. The residents hoped for improvement. According to a resident/tenant named L., at least eight to nine different people independently contacted the management.

However, the complaints went unanswered or were dismissed with reference to data protection. The standard reply was essentially:

S. also reports that she repeatedly sees the same men standing there who seem to be responsible for the young women. She suspects that they are the pimps.

“The suspected lookouts or pimps mostly stay in front of the building and in the entrance area — usually sitting on the plaza outside. What is striking is that they can be seen repeatedly in the same spot over long periods of time — sometimes for hours or throughout the entire day.

Students also regularly observe them inside the building: walking through the hallways, accompanying individual women to the rooms, and apparently staying in the same apartments.

Because of this concentration and their recurring presence, many do not believe these are ordinary clients but rather organized supervisors or pimps.”- S.

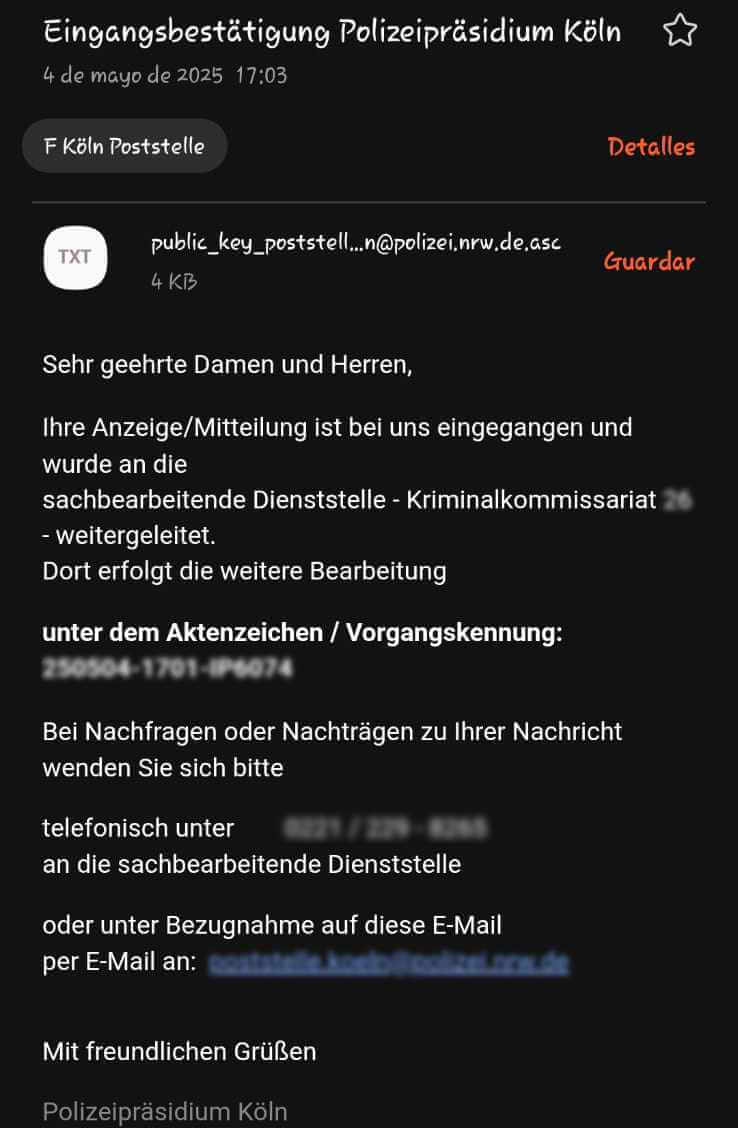

L. alerted the police — providing an audio recording of a crying woman. On the recording, sounds of her being beaten can be heard. Result: no action was taken.

“The police listened to the recording and said: There’s nothing we can do with this.”

– L.

The police were unable to detect any criminal offenses during inspections in the fall.

- Zitat Sat1 Report

From a resident’s noise log:

After Gi. E. moved out (March), Ma. Z. began to occupy the room with new women approximately every one to two weeks. From that point on, there was a noticeable escalation: regular sightings of clients, lookouts, and unfamiliar men inside the building.

What initially sounded like vague suspicions became a troubling pattern for the residents.

Sex advertisements started appearing online — under names like “Trixi,” “Lusy,” and “Xenia.” The photos clearly showed rooms from the dormitory, with furnishings identical to those of the standardized apartments.

For some of the girls, it’s unclear whether they are actually 18. It’s hard to tell.

– Student L.

The number of revolving prostitutes is shocking. It all seems very organized.

– Bewohnerin S.

The following screenshots from the client magazine document user experiences with Trixi, Lucy, and Xenia. The quoted comments reflect the often exploitative and dehumanizing attitudes of some clients and highlight the problematic dynamics present in such forums.

Source references:

Tenant L. repeatedly contacted the property management, complaining about the massive noise that occurs every night. Initially, the management demanded an unspecified number of noise logs over an indefinite period. At the same time, they refused to provide any information about the status of warnings issued or a possible termination of the lease — citing “data protection reasons.”

Repeated mix-ups, harassment, and insinuations

There are regular cases of mistaken identity and harassment. Female students are harassed by clients because they are mistaken for prostitutes. Student Se. recounts a conversation with a client: “I just f*cked with the one upstairs.” Others report attempted break-ins into their rooms by clients. Student Sv. describes a pimp who stands outside the building for hours, watching the women.

One evening, I went out of the building with a friend, and the pimp had already been sitting there for at least three hours, watching people, etc. When we left, he was almost right next to us, so we first went to the right toward the main street—behind a wall where he shouldn’t have been able to see us. After a few minutes, we crossed the street to the kiosk and talked to the shopkeeper. We were the only ones there. Two minutes later, he was really right behind us. We found that really creepy at the time.

- Studentin Sv.

Student Se. describes her first moment of shock:

I was abroad. In early April, I first became aware of the situation that prostitution was taking place there. I had two friends visiting, and we were talking on the stairway in the hallway. A woman (presumably a prostitute) came down, smoked in the hallway, and then went back upstairs with a man. Later, the man came back down. One of my friends spoke to him — it was after midnight, and she didn’t want to buy anything more at the kiosk, so she asked him if he had a cigarette.**

**He replied, “Do you work with the one upstairs?” We said, “No, no,” because we didn’t yet know what it was about. Then the girl (the prostitute) came back down and picked up someone new. He then said to a friend, “Wow, you look really interesting. You have such beautiful hair — is it red or orange?” and flirted with her. The prostitute then warned him, and they went back upstairs together.- Studentin Se.

Student Sv. adds:

By the way, it’s possible that the pimp sometimes stays overnight in the hotel. I’ve occasionally seen him in the stairwell on the 4th floor, going up to the hotel and then back down to room 4.25, where there is also a prostitute.

- Sv.

The uncertainty grows—and with it, the fear. Everyday life is poisoned. What unites the residents is frustration and anger. Despite multiple reports to the police, management, and regulatory authorities, nothing changes on the ground.

The student tenant L. repeatedly follows up with the management. He writes a third noise log, which he continuously updates and sends to the management. According to the management, they need this to issue a third warning and then proceed with terminating the tenant’s lease. However, any mail to Ma. Z. remains unopened in the mailbox.

Despite the first two warnings, Ma. Z. showed no effort to conceal his activities. Shortly before the third and final warning, he even tried to swap his room with a neighbor—without involving the management (Placed). To facilitate this, he sent an acquaintance—a staff member from the “Lost Monk” restaurant—who also regularly cleaned the room after the prostitutes were rotated.

Going public

Despite the suspected eviction notice at the end of April from the management with a two-week deadline to vacate, the situation in the apartment remains unchanged. On May 20, the students finally turn to the press. Their hope is that this will set things in motion to bring about some change.

They send links to advertisements, images, testimonials, and photos of the furnished room on placed.digital. Shortly afterward, outlets such as SAT.1 NRW, EXPRESS, and Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger report on the case.

After the publication of the Kölner Stadt-Anzeiger article, frustrated criticism pours in from the students:

It’s good that the headline says “Property management responds,” even though the police — despite being on site and having evidence — couldn’t find any criminal offenses. 🫠 I find that phrasing a bit too positive, and there’s no real focus on the suffering of the women or the fact that the management didn’t even reply to many complaints.

- A.

The property management responds very late — if at all — despite multiple complaints and reports. What kind of headline is that?

- Se.

On Instagram and Facebook, meanwhile, cynical comments are piling up:

Source: Instagram, Facebook

In the evening, the impression arises that one of the prostitutes is moving out and something is starting to happen. A student discreetly follows the woman and observes her attempting to check into a nearby hostel around 11:49 PM together with a suspected pimp. Neither of them speaks German. The police are informed and carry out a personal check but do not file any charges. Later that evening, the same woman returns to the dormitory.

RTL filmed on site on May 21 but did not broadcast anything. The reason given:

“Good morning xxx, RTL decided the day after our shoot not to air the segment — among other reasons because both rooms are now empty, presumably due to coverage by colleagues from the newspapers and SAT.1. Additionally, this allows us to protect Li. xxx, with whom we openly conducted an interview. We hope this brings peace to Ehrenfeld. Best regards.”

That same evening, “Trixi” was again seen in the building with a client.

Express publishes another article, to which Sv. responds:

The police say there’s no report, but recently a student actually filed one online on May 4th.

- Sv.

I myself called the police on the 14th.

- I.

I called them on February 5th and showed them the audio recording.

- L.

Statements from the police

Below are excerpts from two media reports.

On May 21, the students contacted numerous institutions and specialized agencies to inform them about the documented evidence—including ECPAT, the Federal Criminal Police Office (BKA), Agisra, the umbrella organization KOK, the police, customs, and Solwodi. However, the students only received responses from ECPAT and Agisra: ECPAT confirmed that they had forwarded the information—among others, to the BKA—while Agisra offered to provide comprehensive counseling and support in case of direct contact with those affected. The other agencies did not respond.

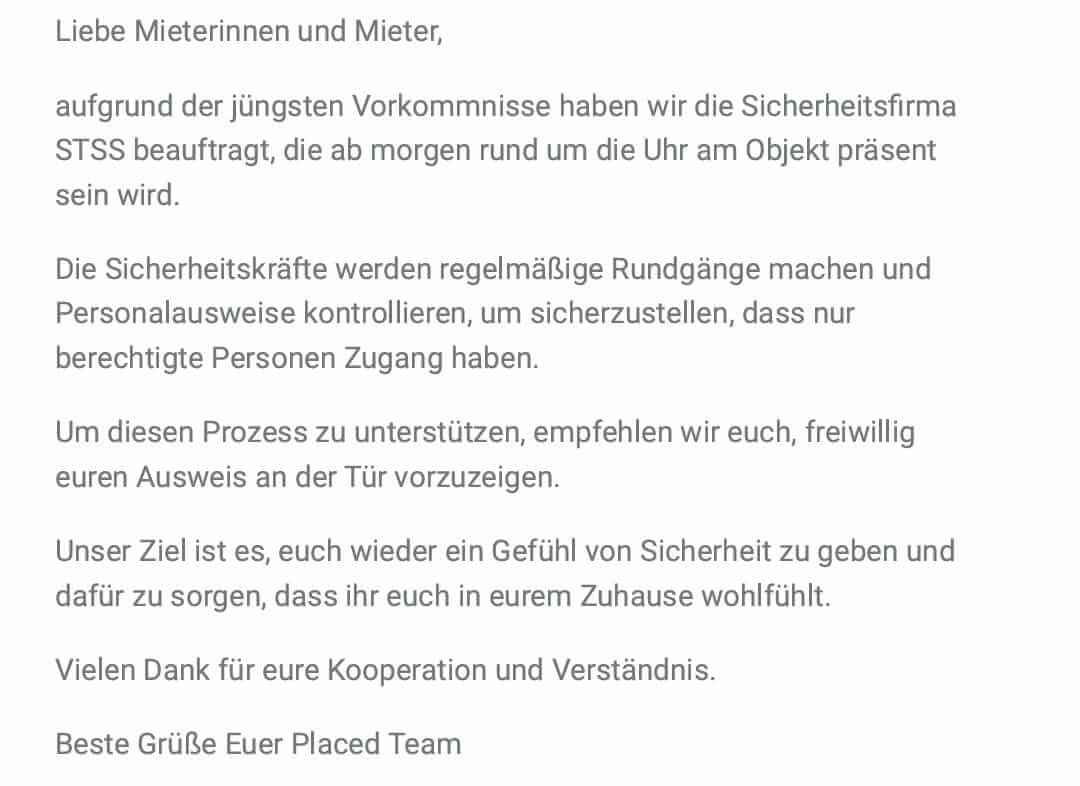

After the media coverage, the property management actually takes action for the first time. They hire a security service and inform the residents by email on May 22. The security service is supposed to monitor the building 24/7.

Despite this, clients continue to enter the building.

Kölner Stadtanzeiger: Razzia im 4711-Gebäude

t-online: Polizei stoppt Prostitution im 4711-Gebäude

On May 24 and 25, 2025, the media reported a raid, but in the WhatsApp group of about 121 students, no one heard anything about it. The security team remains in the building and continues to conduct checks. A. hears suspicious noises coming from the floor above.

I’ve been hearing that above me constantly since I moved in. I always wonder why they move the furniture around so much and stomp so loudly.

- A.

Sv. adds:

This boss at Lost Monk tried to downplay those noises and basically said it was just freaking mice. 😭😭

- Sv.

The security service reports that not only prostitution is taking place in the building, but also hard drug trafficking. They regularly recognize individuals they know from their many years of work in Cologne—especially in the Kalk and Mülheim districts—who are associated with such offenses. However, without concrete evidence, their hands are tied; they can only expel these individuals from the premises if caught in the act. These people often gain access to the building through the adjoining hotel or through doors left open.

Guys, room 305 is occupied again—even though the key was supposedly deactivated.

- L.

This case vividly demonstrates how complex and multifaceted the problem of human trafficking for sexual exploitation is in Germany — and how little it has so far been addressed by society, authorities, and the legal system:

A property management company that reacts late and half-heartedly.

Authorities that wait for formal complaints — while people are exploited daily.

A society that prefers cynical comments over taking responsibility.

And a legal system that allows prostitution but stands helpless against exploitative structures.

The German legal system:

The system is divided: Prostitution is generally legal in Germany (§ 1 ProstSchG – Prostitutes Protection Act), and sex work is recognized as a profession. At the same time, there are strict laws against human trafficking (§ 232 StGB), forced prostitution (§ 232a StGB), and pimping (§ 181a StGB). However, in practice, it is difficult to prove these crimes because they occur under the guise of legal prostitution. Prosecution thus depends on reliable evidence and victim testimony, which victims often hesitate to provide.

Overview of the legal framework:

Prostitutes Protection Act (ProstSchG), §§ 1 ff.:

Regulates the practice of prostitution in Germany, introduces registration requirements, and aims to improve the health and social situation of sex workers.

Criminal Code (StGB), § 232 – Human Trafficking:

Punishes trafficking people for exploitation, such as prostitution, with imprisonment.

StGB, § 232a – Forced Prostitution:

Punishes forcing prostitution through violence or threats.

StGB, § 181a – Pimping:

Criminalizes promoting the prostitution of others for profit.

Applied to the case in Cologne, this means:

As long as the women tell the police they work there voluntarily, the police cannot do much. Despite suspicion of organized structures, police would need to invest enormous resources to independently prove exploitation beyond the women’s statements — a level of effort often impossible given limited staffing.

Indicators suggesting this is not voluntary prostitution:

The women are very young and do not speak German.

They are not independent tenants.

They are visibly organized by a man who sits outside the building daily, handles rent payments, accompanies them outside, and is the contact person for clients — as confirmed by statements on client forums.

Screaming, crying, and women being beaten.

At least one man organizes several women who rotate between rooms.

What should the authorities have done?

At minimum, conduct inspections under the Prostitutes Protection Act: Do the persons involved have permits? Have they received counseling? Are they registered as residents anywhere? Do they have health insurance? None of these checks or consultations took place.

Every place where sexual services are offered requires a permit. An inspection should have been conducted here as well. However, the dormitory is located in a restricted zone where prostitution is prohibited. In addition to the business ban in the dormitory, prostitution is forbidden in this district. This double ban makes a permit for a prostitution venue moot. The authorities should have acted differently given these prohibitions.

The Nordic Model as an alternative?

In countries like Sweden or Norway, the so-called “Nordic Model” applies: not the prostitutes, but the clients are criminalized (§ 4a Prostitution Act in Sweden). The goal is to reduce demand and provide protection for women. It also aims to make it easier and more effective to prosecute human trafficking for sexual exploitation. Critics and supporters debate its effectiveness, but it is clear that such an approach could curb the problem of anonymous clients in dormitories like in this case. Police would have easier options to sanction clients and pimps and thus prevent exploitation.

What if Germany adopted the Nordic Model — where clients, not women, are criminalized? Perhaps fewer older men would roam anonymously into dormitories looking for sex with young Eastern European women whose “employer” lives in the same building.

One thing is clear: Regardless of which laws exist in Germany — they must also be enforced. In this case, even existing laws were not applied. Why is that?

Do we lack resources?

Do we not care?

What if the noise nuisance from the alleged exploitation had not been so loud? Would anyone have acted then?

We must look! A group of young people had the courage not to look away. They document, confront, and oppose — demanding a society that protects instead of turning a blind eye.

It must not be acceptable to us that economic hardship forces many young women from Eastern Europe to prostitute themselves under degrading conditions. Nor should it be acceptable that there is great demand in our country that exploits this hardship for sexual gratification.